Only writing this post to try out the embeddable chart for various Policy Rates, Lending Rates and Short Term Rates which I shared in my earlier post: Live Rates Tracker

The interest rate framework of any economy serves as the critical mechanism through which monetary policy transmits into real economic outcomes. In Nepal, this framework is characterized by a blend of regulatory prescription and market-based elements, shaped by the Nepal Rastra Bank’s (NRB) developmental approach to financial intermediation. Understanding how interest rates are determined, transmitted, and regulated in Nepal requires a thorough examination of three interconnected categories: lending rates, policy rates, and short-term rates. Each category operates within a distinct theoretical and regulatory context, yet they are fundamentally linked through the monetary transmission mechanism that ultimately influences borrowing costs for businesses and households across the country.

The theoretical foundation of interest rate determination rests on the premise that lending rates must compensate lenders for the time value of money, the opportunity cost of capital, expected inflation, credit risk, and operational costs. In market-based systems, these components are typically embedded in a spread above a benchmark rate, allowing for risk differentiation across borrowers and loan characteristics. However, Nepal’s regulatory framework deviates from this conventional approach by explicitly incorporating operating costs into the statutory base rate formula, thereby transforming the base rate from a neutral benchmark into a policy instrument for directed credit allocation. This structural choice has profound implications for how interest rates function in the Nepali financial system, affecting everything from microfinance outreach to large infrastructure project financing.

This article provides a comprehensive theoretical analysis of Nepal’s interest rate framework, drawing on regulatory directives, comparative insights, and the underlying economic logic that shapes the interaction between different rate categories. The discussion addresses not only how rates are technically determined but also why the system operates as it does and what structural challenges emerge from its design.

Theoretical Foundations of Lending Rate Determination

The Standard Decomposition of Lending Rates

In classical financial theory, the lending rate charged by commercial banks represents the sum of several distinct components that together reflect the full cost of providing credit. The foundational decomposition is expressed as:

Lending Rate = Base Rate (Cost of Funds + Policy Stance + Inflation Expectations) + Risk Premium + Tenure Premium + Profit Margin

This decomposition reflects the economic reality that banks must recover their funding costs while accounting for the risks inherent in lending over different time horizons and to borrowers with varying credit profiles. The base rate component captures the opportunity cost of capital and the general level of interest rates in the economy, typically influenced by central bank policy. The risk premium compensates the lender for the probability of borrower default and the expected loss given default. The tenure premium reflects the additional compensation required for lending over longer periods, during which uncertainty about future economic conditions and interest rate movements increases. Finally, the profit margin represents the return that shareholders require on their equity investment in the banking institution.

In market-based systems such as those found in advanced economies, the base rate typically excludes operating costs and profit margins, leaving these to be determined competitively or through regulatory oversight of overall profitability. This design allows for differentiated pricing based on individual borrower characteristics while ensuring that the core funding cost is determined by market forces. The theoretical elegance of this approach lies in its ability to allocate capital efficiently by price discrimination based on risk, with safer borrowers paying lower rates and riskier borrowers paying higher rates that reflect their actual credit profile.

Nepal's Unique Statutory Formula

Nepal diverges significantly from this standard decomposition through the base rate determination procedure which mandates that licensed financial institutions calculate their base rate using a specific regulatory formula:

Base Rate = Cost of Funds + Cost of Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) + Cost of Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) + Operating Cost

This formula explicitly incorporates operating costs into the base rate itself, a design choice that fundamentally alters the economic interpretation of the components that follow. The cost of funds represents the weighted average interest rate on domestic deposits and borrowings, capturing the actual expense that banks incur to acquire the resources they lend. The cost of CRR reflects the opportunity cost of maintaining required reserves with the central bank, which cannot be deployed for earning purposes. Similarly, the cost of SLR captures the return foregone by holding liquid assets in prescribed government securities rather than higher-yielding alternative investments. The operating cost component is calculated as 85 percent of total operating expenses (excluding specific NFRS finance expenses and employee bonuses) divided by average investable funds, ensuring that banks recover their administrative and operational expenses through this mandatory charge.

This structural arrangement means that the premium charged above the base rate in Nepal’s system is conceptually intended to represent only credit risk and maturity risk, with profitability regulated indirectly through interest spread ceilings rather than explicit profit margins. This design is not accidental but reflects a deliberate regulatory philosophy that seeks to socialise banks’ cost recovery while providing the central bank with doctrinal and economic justification for imposing sector-specific interest spread ceilings.

Sector-Specific Premium Caps and Their Theoretical Implications

The NRB’s regulatory framework includes extensive sector-specific caps on the premiums that banks can add to their base rate when lending to different sectors of the economy. For Class A, B, and C institutions, the following caps apply: a maximum premium of 2 percentage points over the base rate for priority sectors including food production, livestock, fisheries, agricultural enterprises (for loans up to Rs. 2 Crore), hospital establishment in underserved areas (up to 100 beds, loans up to Rs. 20 Crore), fruit and herb production, IT park and industrial park construction, residential reconstruction for earthquake-affected families (up to Rs. 25 Lakhs), and wholesale lending to microfinance institutions. For hydropower projects, an even lower cap of 1 percentage point applies for projects that have started exporting electricity (first 5 years of export) and for reservoir-based hydropower projects (entire loan term).

These caps reflect NRB’s developmental mandate to direct credit toward strategically important sectors at affordable rates. However, the theoretical implications are significant: “credit risk is heterogeneous, even within the same sector. One hydropower project is not another hydropower project. Project execution risk, sponsor quality, and hydrology risk are ignored.” The result is a compression of risk differentiation that can lead to adverse selection, where banks preferentially lend to safer borrowers within capped sectors while excluding others who might be creditworthy but face project-specific risks that cannot be priced into the loan.

Policy Rates and the Interest Rate Corridor

Conceptual Framework of the Interest Rate Corridor

The interest rate corridor is a monetary policy framework designed to minimise volatility in short-term market interest rates by defining a range within which these rates should fluctuate. This framework consists of three primary components: the Standing Liquidity Facility (SLF) rate serving as the upper limit, the repo rate serving as the policy anchor, and the Deposit Collection Rate (also known as the Standing Deposit Facility or SDF) serving as the lower limit. The goal of this architecture is to anchor short-term market interest rates, particularly the interbank rate, within a predictable band that facilitates effective monetary transmission.

In Nepal’s current framework, currently, the SLF rate is set at 6.50 percent, the repo rate (policy rate) stands at 4.50 percent, and the SDF rate is set at 2.75 percent. This creates a corridor of 3.75 percentage points within which the interbank rate is expected to trade. The theoretical logic is straightforward: banks with excess liquidity will not lend to each other at rates below the SDF rate because they can earn the same risk-free return by depositing with NRB, while banks needing liquidity will not borrow at rates above the SLF rate because they can obtain emergency funding from NRB at that rate. The repo rate sits between these bounds, serving as the midpoint that NRB aims to influence through its liquidity operations.

The Ceiling Rate: Standing Liquidity Facility (SLF)

The SLF rate represents the maximum interest rate at which banks can borrow overnight liquidity from NRB on demand, using government bills and bonds as collateral. This facility serves as the upper bound of market interest rates and is intended for use when banks face acute liquidity shortages that cannot be met through interbank borrowing. The SLF rate is always higher than the policy rate, reflecting the penalty nature of emergency borrowing and the central bank’s role as lender of last resort.

The economic significance of the ceiling rate lies in preventing excessive borrowing costs during periods of systemic liquidity stress. When many banks simultaneously face CRR pressure or sudden cash outflows, the interbank rate would otherwise spike to levels that could destabilise the financial system. The existence of the SLF rate ensures that no bank needs to pay more than this rate to obtain overnight funding, capping the cost of liquidity stress and preventing contagion through the interbank market.

The Floor Rate: Standing Deposit Facility (SDF)

The SDF rate represents the minimum interest rate that NRB pays on overnight deposits placed by banks with excess liquidity. This facility serves as the lower bound of market interest rates, providing banks with a risk-free return for surplus funds that they might otherwise be compelled to lend at lower rates in the interbank market. The SDF rate is always lower than the policy rate, reflecting the fact that banks are willing to accept a below-policy return in exchange for the safety and certainty of central bank deposits.

The economic significance of the floor rate is to prevent rate collapse during periods of structural liquidity surplus. In Nepal, this situation frequently arises due to strong remittance inflows and seasonal government spending patterns. Without the floor rate, the interbank rate could fall to negligible levels, distorting the pricing of longer-term assets and potentially creating incentives for excessive risk-taking in search of yield. The SDF ensures that “no bank will lend to another bank at a rate lower than the SDF rate, because it can safely deposit funds with NRB instead.”

The Policy Rate: Overnight Repo Rate

The repo rate is the central signaling rate at which NRB conducts its main liquidity operations with banks, serving as the primary instrument for monetary policy signalling and routine liquidity management. In Nepal, the policy rate announced by NRB is explicitly the overnight repo rate, distinguishing it from systems where the policy rate might be a target range or a different administered rate. The repo rate sits at the midpoint of the corridor and serves as the anchor around which NRB aims to keep the interbank rate.

Changes in the repo rate signal NRB’s monetary policy stance: an increase indicates tightening (desire to moderate inflation or cool credit growth), while a decrease indicates easing (desire to stimulate economic activity). However, the effectiveness of this signalling depends on the transmission mechanism working smoothly through the banking system. In Nepal, as will be discussed later, this transmission is often incomplete due to structural features of the base rate system and the prevalence of excess liquidity that keeps interbank rates near the floor rather than the policy rate.

Corridor Level Changes Versus Width Changes

A critical distinction in understanding monetary policy operations is the difference between changing the level of the corridor and changing its width. Corridor level changes involve shifting all three rates (SLF, repo, and SDF) up or down together while maintaining the same width, signalling a change in the overall stance of monetary policy. When NRB raises the corridor level, it signals tightening: borrowing costs throughout the economy are expected to rise. Conversely, lowering the corridor level signals easing, with borrowing costs expected to decline.

Corridor width changes involve altering the distance between the ceiling and floor while potentially leaving the policy rate unchanged or moving it less than the bounds. Narrowing the corridor forces interbank rates closer to the policy rate, reducing volatility and improving policy control. Widening the corridor allows more market-driven interest rate variation, potentially at the cost of increased volatility. NRB rarely changes corridor width in normal times, as width adjustments are primarily technical interventions to manage interbank market behaviour rather than signals of monetary policy direction.

Interaction between: Ceiling SLF, Floor SDF, Policy / Repo Rate, Base Rate and Interbank Rate

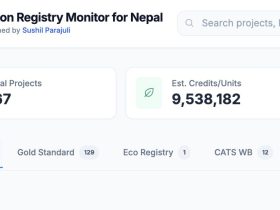

Create and embed your own interest rates graphs using this tool: Interest Rate Tracker

Short-Term Rates and Their Market Roles

Treasury Bills Rate: The Risk-Free Benchmark

Treasury bills are short-term government securities issued with maturities typically ranging from 28 to 364 days, with yields determined through auction-based market mechanisms. The T-bills rate represents the risk-free rate for the Nepali economy, reflecting the government’s cost of short-term borrowing and serving as the benchmark for pricing other short-term financial instruments. Since these securities are backed by the full faith and credit of the government, they carry no credit risk and form the foundation upon which other rates are built.

The T-bills rate is market-determined rather than administratively set, with the auction process revealing investor demand for short-term government paper at different yield levels. This rate reflects not only the government’s liquidity needs but also overall market liquidity conditions, inflation expectations, and the relative attractiveness of government versus corporate debt. In the hierarchy of short-term rates, T-bills typically trade above the reverse repo rate but below the repo rate, reflecting their slightly longer maturity and the fact that they are not a perfect substitute for overnight funds.

The Interbank Rate: Price of Liquidity Among Banks

The interbank rate is the interest rate at which banks lend to and borrow from each other for very short-term periods, typically overnight to a few weeks, without requiring collateral. This rate represents the price of liquidity among banks and is the most sensitive indicator of systemic liquidity conditions. Banks face daily mismatches between deposits and withdrawals, loan disbursements, and statutory requirements for CRR and SLR, creating natural demands for short-term borrowing and lending.

In a well-functioning corridor system, the interbank rate should trade close to the repo rate, pulled toward this anchor by the availability of borrowing at the SLF rate and lending at the SDF rate. However, in Nepal, the interbank market is shallow and liquidity is often structurally surplus, causing the interbank rate to frequently trade closer to the floor rate rather than the policy rate. This divergence weakens the signalling power of the policy rate and complicates monetary transmission.

Reverse Repo and Deposit Auction Rate: Managing Surplus Liquidity

The reverse repo rate represents the return that banks earn when they park excess liquidity with NRB, serving as the floor rate in the interest rate corridor. This facility is used when banks have surplus funds that they cannot profitably lend in the interbank market or through other channels. The reverse repo provides a risk-free alternative that prevents the interbank rate from falling to unsustainable levels during periods of liquidity abundance.

The deposit auction rate is a market-based tool used when NRB needs to absorb structural liquidity surpluses through competitive auctions where banks place excess funds with the central bank for fixed tenors (typically 7 to 14 days). Unlike the reverse repo, which is a standing facility with a fixed rate, the deposit auction rate is determined by market forces and varies based on the amount of liquidity NRB wishes to absorb and the rates banks are willing to accept. This tool is particularly relevant in Nepal during periods of heavy remittance inflows or following large government spending programmes.

Transmission Mechanism and Structural Problems

The Full Transmission Chain

The theoretical transmission chain from policy rates to lending rates operates through a sequence of intermediaries: Policy Rate → Interbank Rate → Deposit Rates → Base Rate → Lending Rates. Changes in the policy rate are intended to flow through this chain, eventually affecting the interest rates that borrowers pay on their loans. However, each step in this chain introduces delays and potential distortions that can weaken or delay the transmission of policy signals.

When NRB raises the policy rate, the immediate effect should be an increase in the interbank rate as banks adjust their short-term lending and borrowing rates. This higher short-term cost should then feed into deposit rates as banks seek to maintain their funding by offering higher rates to depositors. The elevated deposit rates increase the cost of funds component in the base rate formula, eventually raising the base rate itself. Finally, the higher base rate translates into higher lending rates, with the magnitude and timing depending on loan pricing conventions and regulatory requirements.

Structural Problems in Nepal's Base Rate System

Despite its conceptual soundness, Nepal’s base rate system suffers from several structural problems that limit its effectiveness and distort credit allocation. The first major issue is that the base rate is calculated on average historical costs rather than marginal or forward-looking funding costs. “Lending decisions are made at the margin, deposits reprice faster than loans, and during tightening cycles, banks face higher new funding costs but cannot reflect them immediately.” This mismatch can lead to credit rationing rather than price adjustment, as banks may choose to stop lending rather than raise rates transparently.

The three-month average floor creates additional stickiness in lending rates. Banks are prohibited from lending below the average base rate of the last three months, meaning that even if current funding costs fall sharply, lending rates cannot adjust downward correspondingly. This creates downward rigidity in lending rates and slows the pass-through of easing monetary policy, with borrowers failing to benefit quickly from falling interest rates. The base rate thus acts as a ratchet rather than a flexible benchmark, moving up more easily than down.

The excessive regulatory micromanagement of premiums through sector-specific caps has already been discussed, but its consequences bear repetition: mispricing of risk, adverse selection, and the shifting of pricing discretion to non-transparent channels such as fees, covenants, and collateral requirements. Premium rigidity – where premiums stated in offer letters cannot normally be increased during the loan term – leads banks to inflate premiums at origination to protect against future risk, further undermining the intended transparency of the system.

The Infrastructure Finance Mismatch

Long-tenure infrastructure finance, particularly hydropower, faces a fundamental mismatch when priced against the monthly-reset base rate. Infrastructure loans typically have maturities of 15 to 25 years with stable, project-specific cash flows. Applying a short-term funding benchmark to these long-term assets transfers interest rate volatility entirely to borrowers, increasing refinancing and restructuring risk. This contradicts project finance best practice, which typically involves fixed rates or swap-linked structures that hedge interest rate risk over the loan term.

The Transmission Bottleneck

Perhaps the most significant structural problem is that the base rate itself acts as a transmission bottleneck, slowing and dampening the effect of policy rate changes on lending rates. The averaging mechanisms, operating cost preloading, lending floors, and premium rigidity together create a system where “policy rate is fast, base rate is slow, lending rate is slowest.” This transmission lag reduces the effectiveness of monetary policy and can lead to policy overshooting or delayed responses to economic conditions.

The disconnect between the policy rate and lending rates is particularly evident during periods of excess liquidity, which is common in Nepal due to remittance inflows. When liquidity is structurally surplus, the interbank rate trades near the floor rate rather than the policy rate, weakening the signalling effect of policy changes. Banks can earn a risk-free return on excess funds through the SDF, and may not need to adjust deposit and lending rates in response to policy changes. This explains why NRB often relies on liquidity tools in addition to rate tools, employing measures such as CRR adjustments and open market operations to influence credit conditions.

Comparative Perspective: Nepal's Unusual Model

International Comparison of Base Rate Systems

Nepal’s base rate system is unusual in international comparison. India, for instance, moved from the base rate system to the Marginal Cost of Funds-based Lending Rate (MCLR) system and subsequently to an external benchmark system linked to the repo rate. The MCLR partially incorporates operating costs but still differs from Nepal’s approach. OECD countries typically price loans off market benchmarks such as SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) or SONIA (Sterling Overnight Index Average), with operating costs recovered through spreads rather than embedded in the benchmark. Bangladesh partially includes operating costs in its base rate equivalent and has some sector-wise spread caps, while Pakistan does not include operating costs in its benchmark and has weak sector-wise controls.

|

Country |

Operating Cost in Base Rate |

Sector-Wise Spread Caps |

|

Nepal |

Yes |

Yes (extensive) |

|

India (MCLR) |

Partial |

Limited |

|

OECD (SOFR-based) |

No |

Rare |

|

Bangladesh |

Partial |

Yes |

|

Pakistan |

No |

Weak |

This comparison reveals that Nepal’s model is closer to a developmental central banking regime than a market-clearing one. The regulatory philosophy accepts reduced efficiency and flexibility in exchange for stability, directional credit allocation, and political legitimacy. The preloading of operating costs into the base rate is precisely what enables NRB to be prescriptive on interest spreads sector-wise, because it “insulates institutional viability while converting the credit spread into a controllable policy variable.”

Why This Model Persists

From NRB’s perspective, several factors justify the current framework. Financial markets in Nepal remain shallow, with limited instruments for interest rate hedging and risk management. Project appraisal capacity across banks is uneven, potentially leading to misallocation of credit if risk-based pricing were left entirely to market forces. Political economy demands cheap credit for priority sectors, creating pressure for regulatory intervention. Infrastructure and agriculture are strategic sectors that require support for national development objectives.

The trade-off is acknowledged but accepted: efficiency is sacrificed for stability and directed credit allocation. Weak banks are protected by the guaranteed cost recovery embedded in the base rate, efficiency incentives are muted, and cost reduction is not directly rewarded. However, the system provides predictability for borrowers, supports credit flow to priority sectors, and maintains financial stability in a market with limited depth and sophistication.

Understanding Nepal’s interest rate framework requires appreciating both its theoretical foundations and its practical realities. The system is built on a deliberate regulatory choice to embed operating costs within the statutory base rate, enabling NRB to impose sector-specific spread caps while ensuring banks recover their minimum sustainable costs. This transforms the base rate from a neutral benchmark into a policy instrument for directed credit allocation, a design that is unusual in international comparison but consistent with Nepal’s developmental approach to central banking.

The framework’s three pillars – lending rates, policy rates, and short-term rates – are interconnected through a transmission chain that is often incomplete due to structural frictions. The base rate’s averaging mechanisms, floors, and premium rigidity slow monetary transmission, while excess liquidity and a shallow interbank market prevent the policy rate from anchoring short-term rates effectively. These problems are particularly acute for long-tenure infrastructure finance, where the mismatch between short-term benchmarks and long-term assets creates refinancing risk.

For policymakers, the challenge lies in balancing the legitimate objectives of financial inclusion, priority sector lending, and monetary policy effectiveness against the efficiency costs of regulatory prescription. For bankers, the framework demands careful management of interest rate risk and careful pricing that accounts for the constraints imposed by premium caps and premium rigidity. For borrowers, understanding how rates are determined provides insight into the true cost of credit and the factors that may cause rates to change over time.

The Nepal Rastra Bank’s interest rate framework represents a coherent, if unusual, approach to financial regulation in a developing economy context. It is not a broken system but rather a carefully designed one that reflects specific choices about how to balance competing objectives. Understanding these choices – and their theoretical and practical implications – is essential for anyone seeking to navigate or reform Nepal’s financial landscape.

Leave a Reply