1. An Overview of the Non-Life Insurance Industry in Nepal

The non-life insurance sector in Nepal is a well-established component of the country’s financial landscape. As of Fiscal Year 2080/81, the market consisted of 14 active companies that collectively generated a gross premium income of approximately NPR 3,995.85 crores (equivalent to roughly USD 300 million), underscoring the industry’s significant scale (NIA’s Annual Report 2081/82, Annex 22). The competitive landscape is diverse, featuring private domestic insurers, government-owned entities, and foreign branch operations, many of which were in a state of transition, as indicated by the “merged” status of several leading firms during this period.

Table below provides a detailed ranking of these 14 companies based on their gross premium collection for FY 2080/81, highlighting the market leaders and their operational status. Source: Annual Report 2080/81 NIA

S.N. | Company Name | Gross Premium Collection (NPR Crores) | Status |

1 | Shikhar Insurance Company Ltd. | 525.82 | Active |

2 | Sagarmatha Lumbini Insurance Co. Ltd. | 489.38 | Active (Merged) |

3 | Siddhartha Premier Insurance Ltd. | 419.20 | Active (Merged) |

4 | IGI Prudential Insurance Ltd. | 339.91 | Active (Merged) |

5 | Himalayan Everest Insurance Ltd. | 338.43 | Active (Merged) |

6 | United Ajod Insurance Ltd. | 294.73 | Active |

7 | Neco Insurance Ltd. | 287.70 | Active |

8 | Sanima GIC Insurance Ltd. | 251.22 | Active (Merged) |

9 | NLG Insurance Company Ltd. | 246.45 | Active (Foreign Branch) |

10 | The Oriental Insurance Company Ltd. | 210.03 | Active (Merged) |

11 | Prabhu Insurance Ltd. | 170.66 | Active |

12 | Rastriya Beema Company Ltd. | 165.09 | Active |

13 | Nepal Insurance Company Ltd. | 156.65 | Active (Government) |

14 | National Insurance Company Ltd. | 106.16 | Active (Foreign Branch) |

Industry Total | ~3,995.85 |

The industry’s product portfolio is dominated by a few key lines of business. Motor insurance is the largest segment, contributing 30-32% of total premiums, driven by a high volume of policies. Property (Fire) insurance follows as the second-largest segment (25-28%), covering infrastructure and buildings, while Engineering insurance (12-15%) represents high-value premiums from construction projects. Other segments include Miscellaneous (10-12%), heavily subsidized Agriculture (4-5%), and specialized lines like Aviation and Marine (each 2-3%). Micro-insurance remains an emerging sector at under 1% of the market (Source: Derived from Beema Pratibimba Industry Aggregates).

The distribution of policies issued, detailed in Table below, clearly reflects this portfolio structure, with motor policies constituting the highest count for every company, highlighting the volume-driven nature of this segment.

Company Name | Motor | Property (Fire) | Agriculture | Engineering | Marine | Micro (Laghu) | Others | Total Policies |

Shikhar Insurance | 132,961 | 38,074 | 32,811 | 15,322 | 5,795 | 63,377 | 14,324 | 309,863 |

Siddhartha Premier | 174,549 | 48,891 | 5,167 | 21,500 | 17,071 | 87 | 13,549 | 298,755 |

United Ajod | 164,815 | 19,368 | 12,514 | 2,706 | 13,433 | – | 14,976 | 299,289 |

Neco Insurance | 188,414 | 68,711 | 7,369 | 4,358 | 1,421 | 5,846 | 14,639 | 291,817 |

Sagarmatha Lumbini | 167,044 | 46,481 | 5,889 | 1,697 | 11,693 | 3 | 9,251 | 279,398 |

Himalayan Everest | 60,190 | 10,271 | 13,839 | 698 | 2,158 | 12 | 192,604* | 280,429 |

IGI Prudential | 85,146 | 16,926 | 20,987 | 572 | 3,565 | 11,473 | 3,603 | 222,162 |

Nepal Insurance | 104,914 | 43,118 | 3,649 | 1,435 | 3,361 | 2 | 7,263 | 194,931 |

NLG Insurance | 135,615 | 31,510 | 27,601 | 2,532 | 5,500 | 11,477 | 7,121 | 221,496 |

Prabhu Insurance | 69,809 | 15,282 | 1,272 | 1,150 | 2,746 | 1,265 | 1,194 | 123,873 |

Sanima GIC | 65,690 | 11,143 | 1,732 | 918 | 6,579 | 1,732 | 3,074 | 132,429 |

The Oriental | 21,856 | 3,578 | 3,484 | 496 | 2,930 | 152 | 1,446 | 44,725 |

National Insurance | 8,186 | 2,451 | 1,303 | 427 | 3,529 | 6 | 7,184 | 28,271 |

Rastriya Beema Co. | 89,171 | 9,087 | 4,556 | 292 | 121,143 | – | 12,586 | 151,669 |

Source: Annual Report 2080/81, Anusuchi 12 & 21, *Note: Himalayan Everest’s high count in “Others” is likely due to short-term or travel policies.

Financially, the industry held total assets amounting to approximately NPR 15,023.48 crores with an aggregate equity of NPR 7,633.72 crores. Table below shows the financial standing of each company, with Rastriya Beema Company Ltd. holding the largest asset base, a position influenced by its government ownership.

S.N. | Company Name | Total Assets (NPR Cr) | Total Equity (NPR Cr) |

1 | Rastriya Beema Company Ltd. | 2,408.86 | 1,730.24 |

2 | Siddhartha Premier Insurance Ltd. | 1,549.77 | 770.57 |

3 | Sagarmatha Lumbini Insurance Co. Ltd. | 1,515.10 | 627.12 |

4 | Shikhar Insurance Company Ltd. | 1,380.45 | 582.09* |

5 | IGI Prudential Insurance Ltd. | 1,106.72 | 576.88* |

6 | Neco Insurance Ltd. | 1,094.75 | 499.03* |

7 | Himalayan Everest Insurance Ltd. | 1,051.93 | 525.89 |

8 | NLG Insurance Company Ltd. | 877.53 | 405.42* |

9 | Sanima GIC Insurance Ltd. | 824.72 | 303.37* |

10 | United Ajod Insurance Ltd. | 734.19 | 415.18* |

11 | Prabhu Insurance Ltd. | 697.83 | 300.40* |

12 | Nepal Insurance Company Ltd. | 652.81 | 376.06 |

13 | The Oriental Insurance Company Ltd. | 629.33 | 276.11* |

14 | National Insurance Company Ltd. | 499.49 | 44.64* |

Industry Aggregate | ~15,023.48 | ~7,633.72 |

Source: Total Assets from Annual Report NIA; Total Equity for companies was calculated from Annex 18 of the Annual Report 2081/82.*

A comprehensive view of key performance indicators, including profitability and reinsurance dependence, is presented in Table below. The data shows that most companies were profitable, with Siddhartha Premier reporting the highest net profit of NPR 71.32 crores, while National Insurance reported a net loss of NPR 62.39 crores (Annual Report 2081/82, Annex 13). The industry’s heavy reliance on reinsurance is evident, with companies like Prabhu Insurance ceding around 72% of their premiums, a common practice for risk mitigation.

Company Name | Status | Gross Premium (NPR Cr) | Total Policies | Total Assets (NPR Cr) | Net Profit (NPR Cr) | % Premium Ceded to Reinsurers | Solvency Ratio |

Shikhar Insurance | Active | 579.42 | 309,863 | 1,380.45 | 45.27 | ~69% | 2.60 |

Sagarmatha Lumbini | Merged | 500.21 | 279,398 | 1,515.10 | 40.32 | ~58% | 2.75 |

Siddhartha Premier | Merged | 431.03 | 298,755 | 1,549.77 | 71.32 | ~49% | 3.18 |

Himalayan Everest | Merged | 410.05 | 280,429 | 1,051.93 | 53.23 | N/A | 3.32 |

IGI Prudential | Merged | 366.57 | 222,162 | 1,106.72 | 36.49 | ~70% | 3.42 |

Neco Insurance | Active | 328.11 | 291,817 | 1,094.75 | 55.08 | N/A | 3.84 |

NLG Insurance | Active | 306.49 | 199,026 | 877.53 | 16.11 | ~61% | 3.42 |

United Ajod | Merged | 278.35 | 299,289 | 734.19 | 21.64 | N/A | 2.73 |

Sanima GIC | Merged | 270.33 | 132,429 | 824.72 | 35.03 | N/A | 2.62 |

The Oriental | Foreign Branch | 210.03 | 44,725 | 629.33 | 8.29 | N/A | 2.65 |

Nepal Insurance | Active | 203.75 | 194,939 | 652.81 | 31.64 | N/A | 4.33 |

Prabhu Insurance | Active | 166.93 | 123,873 | 697.83 | 21.19 | ~72% | 4.66 |

Rastriya Beema Co. | Govt. Owned | 165.09 | 151,669 | 2,408.86 | 42.76 | ~69% | N/A |

National Insurance | Foreign Branch | 106.16 | 28,271 | 499.49 | (62.39) | N/A | 1.67 |

Source: Gross Premium, Policies, Net Profit, Solvency Ratio: Annual Report 2081/82; Assets; % Ceded: Calculated from FS, Annual Report of NIA and Annex 22.

The financial data reveals a generally healthy and profitable industry, albeit with a high dependence on reinsurance and significant variation in the size and performance of its constituent companies.

2. Regulatory Framework for Hydropower Project Insurance in Nepal

The insurance framework for hydropower projects in Nepal is meticulously defined by a combination of the Insurance Act 2079, the Property Insurance Directive 2080, and various regulatory decisions from the Nepal Insurance Authority (NIA). This framework mandates a bifurcated approach, separating coverage into two distinct phases: Construction and Operation. The NIA exercises strict control through a “Tariff” regime with fixed rates and a “Non-Tariff” regime with guideline-based pricing to ensure market solvency and standardized coverage across the sector.

2.1 The Construction Phase: Engineering Insurance (Non-Tariff Regime)

During the development phase, hydropower projects fall under Engineering Insurance, which is classified as a “Non-Tariff” business. This means premiums are determined by underwriters based on risk assessment but are subject to the NIA’s minimum guidelines to prevent underpricing, as outlined in the “Minimum Premium Rate for Non-Tariff Insurance Business Guidelines.”

Several specific policy types cater to the unique risks of construction:

- Contractors’ All Risk (CAR): Covers civil works such as dams, tunnels, and powerhouses against physical loss or damage. A critical regulatory provision is the mandatory deductible (excess), which for “Act of God” claims is often set at 10% of the claim amount or 1% of the Sum Insured, whichever is higher. Example: During tunnel excavation for a 45 MW project, a collapse due to unexpected weak rock strata after monsoon rainfall damaged lining works and equipment. The claim was accepted under CAR, with the mandatory “Act of God” deductible applied before indemnifying repair costs (Surveyor Verification Report).

- Erection All Risk (EAR): Covers the installation of electro-mechanical equipment like turbines and generators. Standard coverage includes a testing period (typically 4 weeks to 3 months) for risks during trial operations. Example: A turbine runner was dropped and damaged due to a failed crane sling during installation. This was treated as an EAR claim, covering accidental damage prior to commissioning, and repair costs were paid after technical assessment (Project Erection Log).

- Marine-Cum-Erection (MCE): Combines transit risk for machinery from the manufacturer to the project site with erection risks. Example: A transformer imported from India was damaged when its transport truck overturned on a hilly road. The claim was admitted under the transit section of the MCE policy, and replacement costs were indemnified (Marine Survey Report).

- Third Party Liability (TPL): Covers liability for bodily injury or property damage to third parties, often bundled with CAR/EAR policies. Example: Blasting for a tunnel project caused debris to damage a nearby house and injure a resident. The TPL coverage attached to the CAR policy responded, covering medical expenses and property repair costs (Third-Party Claim File).

A critical and often disputed regulatory clause involves the Maintenance Period (Defect Liability Period). Policies must clearly define if coverage is for “Extended Maintenance” or a wider scope. A key precedent was set in the Melamchi Water Supply Project case, where regulators clarified that an active Maintenance Period clause typically covers damages from construction defects or contractor negligence, but excludes “Act of God” events unless specifically purchased as an add-on (NIA Adjudication, Melamchi Case).

2.2 The Operational Phase: Property Insurance (Tariff Regime)

Once commissioned, the project shifts to Property Insurance under a strict Tariff regime. Premium rates are fixed by the Property Insurance Directive, 2080, and cannot be altered by insurers. The tariff structure for hydropower projects is as follows:

Component | Rate / Calculation | Details |

Basic Premium Rate | Rs 2.00 per thousand (0.20%) | Applied on the Total Sum Insured (Civil + Electro-mechanical assets). |

Consequential Loss (C-Loss) | Variable based on Indemnity Period | Covers Loss of Profit (Revenue) due to plant shutdown. Rates are: 3 Months (125% of Basic Rate), 6 Months (200%), 12 Months (300%). |

Terrorism/Malicious Damage | Rs 0.20 – 0.50 per thousand | Optional add-on for Riot, Strike, Malicious Damage, Sabotage, Terrorism (RSMDST). |

Examples of Operational Phase Claims:

- Property Damage: A sudden flood damaged the powerhouse floor and equipment after commissioning. The physical damage was assessed and indemnified under the Tariff-regime property insurance after deductible adjustment (Claim File: Flood Damage).

- Consequential Loss Scenarios:

- Flood: A major flood damaged turbines, causing a four-month shutdown. Beyond property damage, the Consequential Loss (C-Loss) coverage was triggered, and lost net profit during the indemnity period was paid (C-Loss Calculation Sheet).

- Mechanical Failure: A generator bearing failure caused a three-month shutdown. Revenue loss during the outage was claimed and paid under the C-Loss coverage, using energy generation data and PPA tariffs (Engineering Report & PPA).

- Grid Failure Linkage: A fire in the switchyard disconnected the plant for five months. After property damage was indemnified, the 12-month C-Loss cover was triggered for income loss (Grid Dispatch Records).

- Terrorism/Malicious Damage: Vandalism to transformers during a politically sensitive period was covered because the project had the optional RSMDST add-on, leading to indemnification of repair costs (Police Report & Surveyor Assessment).

2.3 Claim Settlement & Regulatory Safeguards

The NIA has enforced specific frameworks to protect developers from delayed claims:

- Timelines: Insurers must settle claims within 15 days of receiving the surveyor’s final report. Any delay requires a written explanation (Insurance Act 2079, Section 65).

- Surveyor Appointment: For large claims, independent surveyors are appointed. The NIA can intervene if a surveyor delays the report beyond 15 days of a site visit.

- Dispute Resolution: The NIA acts as a quasi-judicial body. A notable case is Upper Dordi A, where the insurer rejected “Debris Removal” costs, arguing the debris came from upstream. The NIA ruled that if the policy covers debris removal, the origin is irrelevant, forcing the insurer to pay (NIA Ruling, Upper Dordi A Case).

2.4 Financial & Risk Management Requirements

Given the catastrophic nature of hydro risks (e.g., GLOFs, floods), the NIA imposes strict financial controls:

- Reinsurance: Insurers must have robust treaties with rated international reinsurers and cannot retain more than 5% of their net worth on a single risk (Reinsurance Directive).

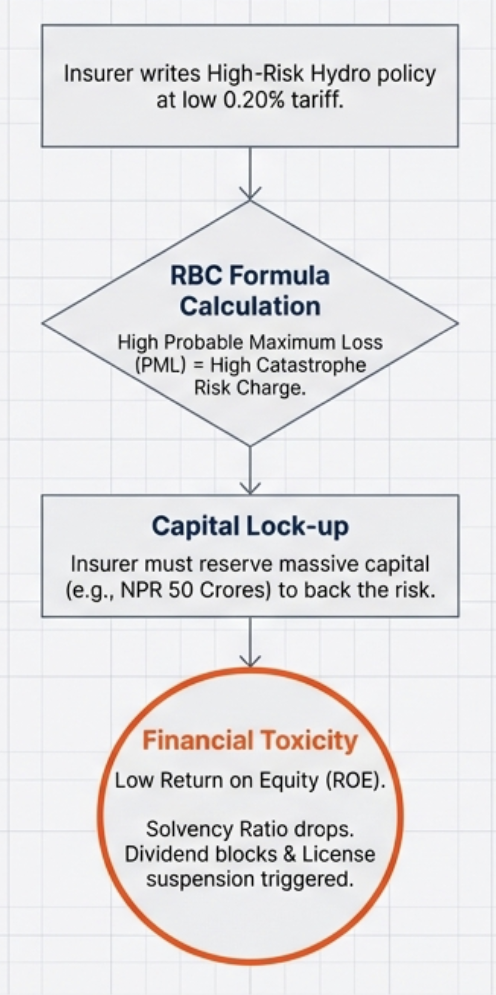

- Risk-Based Capital (RBC): Under the RBC Directive, insurers must hold capital charges proportional to the “Catastrophe Risk” from hydropower projects to ensure solvency.

- Consortiums/Pools: For large risks, policies are issued via a consortium where multiple insurers share the risk (e.g., 41% Lead Insurer, 59% others).

2.5 Policy Gaps and Sovereign Risk

It is important to note that the Hydropower Development Policy 2001 and the Electricity Act 1992 contain no specific mandates for insurance, leaving the Insurance Act as the primary regulator. A significant market issue is that developers often purchase the “minimum viable product” to satisfy loan covenants, resulting in policies with low sub-limits and high deductibles that are inadequate during a total loss scenario. Furthermore, as the sole off-taker and a major generator, the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) has historically practiced “self-insurance” due to financial constraints. This creates a massive contingent liability for the sovereign balance sheet, where the cost of reconstructing a failed mega-project competes directly with other national budget priorities.

3. Insurance Coverage for NEA's Hydropower Projects

The Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) plays a pivotal role in the nation’s power sector, both as a generator and as the primary off-taker. As of the end of Fiscal Year 2024/25, Nepal’s total installed generation capacity reached 3,591 MW. Within this system, NEA’s own generating facilities—including hydro, thermal, and solar—account for approximately 661.57 MW, representing about 18.4% of the total capacity. When combined with the 646.4 MW contributed by projects owned by NEA subsidiaries, the combined capacity under the NEA umbrella amounts to roughly 1,308 MW, or 36.4% of the national total (NEA Annual Report, FY 2024/25).

The approach to insuring these substantial assets is bifurcated between construction and operational phases, with distinct practices for each. During the construction phase, public infrastructure projects, including those owned by NEA, are mandatorily insured. This requirement is explicitly stipulated by the Public Procurement Act, 2063 (Section 64) and the Public Procurement Regulations, 2064 (Rule 112), which mandate that public entities must secure insurance for construction works, equipment, and materials against loss or damage. This practice is evidenced in real cases; for instance, a documented dispute involving NEA concerned a transformer damage claim that was covered under a Marine-Cum-Erection (MCE) policy, confirming that NEA assets are insured during transit and erection (NIA Dispute Resolution Case File). Furthermore, the severe flood damage in 2024 to the Upper Tamakoshi project, a NEA subsidiary, led to the submission of claims amounting to NPR 2 billion for civil and electromechanical works, underscoring the reliance on external commercial insurance for large projects during this phase.

However, the insurance posture shifts significantly once projects become operational. For private Independent Power Producers (IPPs), the regulatory framework provides a clear cost structure under the Property Insurance Directive, 2080. This directive sets a mandatory basic premium rate of 0.20% (Rs 2.00 per thousand) of the sum insured for hydropower assets. Additionally, IPPs typically purchase add-ons: Consequential Loss (Loss of Profit) coverage, priced at 125% to 300% of the basic rate depending on the indemnity period, and Terrorism (RSMDST) coverage at an additional 0.02% to 0.05%. In total, this brings the typical insurance cost for a privately-owned hydropower project to approximately 0.65% to 0.8% of the asset value annually.

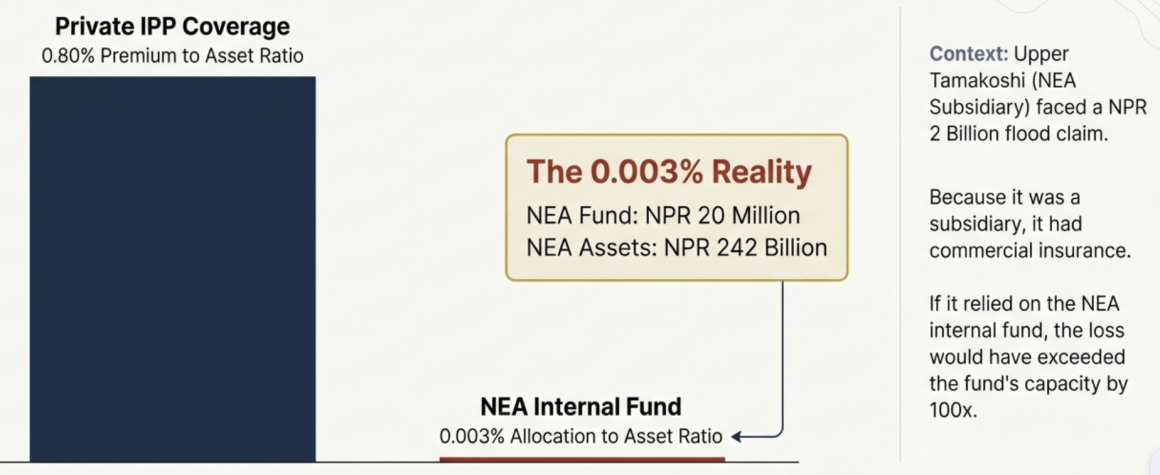

In stark contrast, NEA relies primarily on a self-insurance mechanism for its operational assets. The authority maintains an internal Insurance Fund, for which its accounting policy specifies an annual allocation of NPR 20 million (2 Crore), provided it operates at a profit. This fund is expressly intended to cover potential losses to property, plant, and equipment (PPE). To contextualize this amount, NEA’s total PPE was provisionally valued at NPR 242.0 billion in FY 2024/25. Therefore, the NPR 20 million allocation represents a mere 0.008% of the PPE base. When measured against NEA’s total assets of NPR 683.9 billion, the allocation is even smaller, at approximately 0.003% (NEA Financial Statement, FY 2024/25).

These numbers highlight a critical disparity. While the regulatory framework ensures robust insurance during construction and mandates specific cost structures for private operators, NEA’s operational self-insurance mechanism is severely underfunded. The allocation of 0.003% to 0.008% of asset value stands in stark contrast to the 0.65% to 0.8% typical for insured private projects, demonstrating that NEA’s vast portfolio of operational assets is profoundly underinsured, creating a significant contingent liability for the national treasury.

4. The Bill of Quantities as the Basis for Sum Insured and Premiums

A prevailing trend within Nepal’s hydropower sector is the practice of determining insurance coverage strictly “on the basis of the Bill of Quantities (BOQ).” In professional terms, this means that Contractors’ All Risk (CAR) and Erection All Risk (EAR) policies are underwritten, and claims are settled, by directly mirroring this contractual document—which lists every material and work item—rather than being driven by an independent assessment of the actual risks and replacement values. This approach, while simplifying the initial insurance purchase, creates a rigid framework that often leads to significant disputes when a loss occurs, as detailed in several regulatory cases.

The core of this trend is that the Sum Insured for the policy is set precisely at the Total Contract Value derived from the BOQ. This transforms the insurance policy into a financial reflection of the construction contract, where an item is considered insured if, and only if, it is explicitly listed in the BOQ. However, this reliance becomes a “dispute trap” during claim assessment, as surveyors use the same BOQ rates to validate losses, leading to several documented issues.

First, valuation disputes arise when BOQ rates do not reflect current market conditions. For instance, in the NIA dispute of the case of Pipul Power Ltd., the surveyor calculated the claim amount by applying the rates specified in the BOQ to the quantity of damaged materials. The critical issue here is that if market prices have risen due to inflation between the contract signing and the loss event, the BOQ rate will be insufficient to cover the actual replacement cost, leaving the developer underinsured. Conversely, claims are often reduced if the amount sought exceeds the specific allocation within the BOQ, regardless of real-world costs.

Second, there is a critical gap between contractual coverage and physical presence on site. A common misconception among developers is that an item listed in the BOQ is covered from the moment of purchase. However, a ruling by the regulator NIA in a dispute involving Neco Insurance clarified the reality. The regulator affirmed that CAR policies typically only cover items once they are physically present at the construction site. Therefore, even if materials like cement or steel rods are itemized in the BOQ, damage occurring during transit or before reaching the designated site falls outside the policy’s scope. This “BOQ trend” can create a false sense of security regarding off-site materials.

Finally, the strict adherence to the BOQ can lead to the exclusion of essential but non-listed items. This was evident in the Bajra Guru Construction case, where a claim for “Clearance of Debris” and damage to stored materials was rejected. The regulator’s rationale was that the BOQ did not explicitly list “storage of excavated materials” or include specific terms for debris clearance in that particular context. Because the insurance was strictly bound to the BOQ, and the BOQ was silent on these auxiliary but necessary works, the claim was denied. This demonstrates how a narrow, BOQ-centric approach can fail to address the comprehensive risks inherent in a complex construction project.

5. The Evolution of Bancassurance: Sales & Regulated Loan-Protection

The bancassurance system—a portmanteau of ‘bank’ and ‘assurance’—represents a significant distribution channel within Nepal’s insurance landscape. This model designates Banks and Financial Institutions (BFIs) as “Institutional Agents” (Sansthagat Abhikarta) for insurance companies, leveraging their extensive customer bases and branch networks to sell life and non-life insurance products under a formal agreement. To operate in this capacity, banks must obtain a license from the Nepal Insurance Authority, firmly establishing their role within the regulatory framework.

This system was introduced with a clear objective: to address the critical challenge of low insurance penetration by utilizing the established, widespread infrastructure of the banking sector. The strategic goal was to reach both rural and urban populations who had bank accounts but remained uninsured, thereby enhancing alternative distribution channels as emphasized in the NIA’s own strategic plans. For insurance companies, bancassurance offered a cost-effective solution, allowing them to expand their market reach without the significant capital expenditure of building new branch networks.

However, the initial “open” bancassurance model, which positioned banks as sales agents for a wide range of general policies, became plagued by malpractice, leading to a decisive regulatory shift. The system has now been fundamentally restructured from a broad sales-agent model to a strictly regulated “loan-protection” framework. This evolution was driven by several key interventions aimed at curbing systemic abuses.

A primary issue was conflict of interest and governance. Banks were found to be holding premium payments in their own accounts to profit from the float, rather than transferring the funds to the insurance companies. To eliminate this, the Corporate Governance Directive now mandates that premiums collected by a bank must be deposited into the insurer’s account within seven days, stripping banks of the ability to misuse these funds for their own liquidity.

Furthermore, the scope of bancassurance was sharply narrowed. Recent directives indicate that banks are now primarily restricted to facilitating insurance that is directly linked to their core lending business, such as Credit Life insurance and property insurance for loan collateral, rather than acting as general salespoints for the public.

A major catalyst for this restriction was the widespread problem of “forced selling.” Banks were compelling borrowers to purchase policies from a specific partner insurer as a condition of the loan. The regulator now explicitly forbids this practice, mandating that banks cannot force a customer to choose a specific insurer and must provide clear information about the policy. This addressed the previous opaque practice where banks would deduct “insurance charges” from loan disbursements without transparently explaining the premium calculation or coverage terms.

Finally, the reform addressed critical coverage gaps in “Credit Life” policies. Instances where banks failed to renew policies or refund premiums when loans were closed early left borrowers unprotected after paying for coverage. New rules now require pro-rata refunds or clear terms for policy continuation if a loan is settled ahead of schedule, ensuring fairness and transparency for the consumer.

In essence, the bancassurance system in Nepal has undergone a fundamental transformation. It has evolved from a potentially disruptive sales channel riddled with conflicts of interest into a tightly regulated mechanism focused solely on securing the bank’s loan collateral and protecting the borrower, thereby aligning the interests of the bank, insurer, and customer more effectively.

6. Comparative Analysis of Premium Costs: Hydropower vs. Other Properties

When evaluating the cost of insurance, hydropower projects occupy a middle ground in the risk classification spectrum. While they are not as hazardous as industries involving explosives, their insurance is structured with a base tariff and mandatory add-ons that make the total cost significantly higher than that for standard property types.

The foundational cost is determined by the Nepal Insurance Authority’s mandatory tariff, as outlined in the Property Insurance Directive 2080. The following table, derived from the directive, provides a clear comparison of base premium rates across different property categories, showing exactly where hydropower stands.

Property Type | Risk Category | Base Premium Rate (Per Thousand) | Rate in % | Cheaper/Costlier than Hydro? |

Residential (Home) | Very Normal (Ati Samanya) | Rs 0.50 | 0.05% | 4x Cheaper |

Brick/Stone Quarry | Normal (Samanya) | Rs 1.50 | 0.15% | 25% Cheaper |

Hydropower Project | Hydro/Utility | Rs 2.00 | 0.20% | (Benchmark) |

General Industry | Medium Risk (e.g., Ice Cream, Optical Fiber) | Rs 2.00 | 0.20% | Equal |

Hazardous Goods | High Risk (e.g., Plastics, Matches)* | > Rs 2.00 | > 0.20% | Costlier |

Source: Property Insurance Directive 2080, Annex 15 (Hydro) & Annex 16 (General Property)

However, the base rate is only part of the story. What makes hydropower insurance particularly expensive is the “add-on” factor. Unlike a standard building, where the base rate is often the final cost, hydropower projects are typically required by lenders to purchase Consequential Loss (CLLO) coverage. This add-on carries a significant premium multiplier, drastically increasing the total cost.

- Material Damage Premium: 0.20% (Base).

- Loss of Profit Premium (12 Months Indemnity): 300% of Base Rate = 0.60% .

- Total Effective Rate: ~ 0.80% (0.20% + 0.60%).

This means a hydropower project effectively pays roughly 0.80% of its insured value annually, whereas a commercial building typically pays only 0.15% – 0.20%, and a home pays just 0.05%.

It is also important to distinguish between phases of the project. Hydropower insurance is generally cheaper during the Operational Phase (0.20% base tariff) compared to the Construction Phase. During construction, projects are covered under Contractors’ All Risk (CAR) policies, which are Non-Tariff but regulated by “Minimum Premium Rate” guidelines to prevent underpricing, reflecting the higher risks of landslides and floods during excavation. Once operational, the risk profile decreases, and the fixed property tariff of 0.20% applies.

In summary, while the base tariff for hydropower is comparable to general industry risks, the effective cost is substantially higher due to the essential purchase of Consequential Loss coverage, making it one of the more significant insurance expenses for asset owners in Nepal.

7. Coverage and Exclusions: Insured Perils under Standard Property Insurance in Nepal

The scope of property insurance in Nepal is explicitly defined by the Property Insurance Directive, 2080 (Sampatti Beema Nirdeshan) and standard policy wordings. Coverage is not all-encompassing; it protects against physical loss or damage caused by a specific list of events, while clearly excluding others unless separately endorsed. The following table details the incidents that are covered under a standard policy.

Category | Covered Incidents | Source |

Fire & Explosion | • Fire (Aaglagi): Actual ignition/burning. | Property Insurance Directive, 2080 |

Natural Disasters | • Earthquake (Bhukampa): Shock and fire following earthquake. | Property Insurance Directive, 2080 |

Impact & Air Risks | • Aircraft Damage: Damage from aircraft or aerial devices dropping articles. | Standard Policy Wording |

Social Risks | • Riot, Strike & Malicious Damage (RSMD): Physical damage caused by public unrest, strikes, or vandalism (Huldanga/Hadtal/Todfod). | Property Insurance Directive, 2080 |

Others | • Missile Testing Operations | Standard Policy Wording |

As the table demonstrates, the policy provides a broad safety net against significant natural catastrophes like earthquakes, floods, and landslides, as well as common man-made incidents like fire and impact damage. However, the directive and standard terms also specify a critical list of exclusions. These are events or conditions for which coverage is not provided unless a specific add-on policy is purchased or the peril is explicitly included by endorsement.

Category | Excluded Incidents | Reason/Detail | Source |

Financial | Consequential Loss (Loss of Profit) | The policy covers material damage only. Loss of income due to business stoppage is excluded unless a separate “Consequential Loss” or “Business Interruption” policy is bought. | Property Insurance Directive, 2080 |

Theft | Burglary & Theft (Chori) | Theft of goods during or after a fire/disaster is generally excluded. “Housebreaking” requires a separate Burglary policy. | Standard Policy Wording |

Technical | Electrical Machine Failure | Damage to electrical appliances (e.g., dynamos, motors) caused by over-running, short-circuiting, or self-heating is excluded. Only if a fire spreads from the machine to other property is the spread covered. | Standard Policy Wording |

War & Nuclear | War & Radioactivity | War, invasion, civil war, mutiny, and nuclear radiation/contamination are absolute exclusions. | Property Insurance Directive, 2080 |

Assets | Valuables & Documents | Bullion, jewelry, manuscripts, plans, drawings, and cash are excluded unless specifically declared and insured. | Standard Policy Wording |

Human Factor | Willful Negligence | Damage caused by the insured’s own intentional act or gross negligence. | Standard Policy Wording |

Process | Fermentation/Spontaneous Combustion | Damage caused by the property’s own natural heating (e.g., coal, hay) is excluded unless it causes a fire. | Standard Policy Wording |

In practice, this means that while a hydropower project is covered for direct damage from a flood, it would not be compensated for the lost revenue during the shutdown (unless it had a Consequential Loss add-on). Similarly, damage from a simple electrical fault within a transformer is excluded, but if that fault caused a fire that burned the powerhouse, the fire damage to the building would be covered. Understanding these delineations between covered perils and explicit exclusions is fundamental to recognizing the limits of a standard property insurance policy and the need for specialized coverages.

8. Investment Mandates: Insurance Companies as Financiers of Hydropower

The role of insurance companies in Nepal’s hydropower sector extends far beyond risk mitigation; they are pivotal institutional investors. This is a deliberate strategy enforced by the Nepal Insurance Authority (NIA) through the Insurer Investment Directive, 2082 (2025) and associated regulatory documents. The directive explicitly categorizes Hydropower, Solar, and Renewable Energy as priority sectors, mandating that insurers diversify their portfolios beyond bank deposits and actively finance national infrastructure development. This framework creates a circular economy where premiums collected from the public are reinvested into the very projects that insurers also insure.

8.1 The Regulatory Mandate for Different Insurers

The investment rules are tailored to the specific liquidity profiles and strategic roles of different types of insurers.

- Life Insurers (Jeevan Bimak)

Life insurance companies manage long-term funds with a 15-20 year horizon, making them ideal investors for long-gestation projects like hydropower.

Investment Limit: Life insurers can invest up to 10% of their Total Investment Portfolio in the combined “Agriculture, Production, Tourism, and Hydropower” category.

Permissible Vehicles: This allocation can be directed towards: Equity (Shares): Investment in the ordinary shares of Public Limited Companies established for hydropower, renewable energy, and electricity transmission lines. Debentures/Bonds: Investment in corporate bonds or debentures issued by these hydropower companies.

Key Condition: The investee company (the hydropower project) must be a Public Limited Company. This differs from bank investments, where insurers can invest freely in “A” class institutions. The 10% cap is designed to prevent over-concentration risk in the hydropower sector specifically. - Non-Life Insurers (Nirjiwan Bimak)

Non-life insurers deal with short-term contracts (1 year), so their liquidity requirements are tighter. Despite this, they are authorized significant exposure to hydropower.

Investment Limit: Non-Life insurers are also authorized to invest up to 10% of their Total Investment Portfolio in hydropower and renewable energy sectors.

Scope of Investment: The directive explicitly lists permissible areas: “Hydropower, Solar Energy, Renewable Energy Projects, Cable Cars, Roads, and Electricity Transmission Lines”.

Restriction: Similar to life insurers, the investment must be in Public Limited Companies. A critical additional safeguard is that investment in a single project cannot exceed 5% of the insurer’s total investment portfolio, ensuring diversification and risk mitigation. - Reinsurers (Nepal Re / Himalayan Re)

Domestic reinsurers hold significant capital and are strategically encouraged to retain wealth within the national economy.

Investment Limit: Reinsurers can invest up to 10% of their Total Investment Portfolio in the “Agriculture, Tourism, and Hydropower” category.

Strategic Fit: This is particularly relevant as reinsurers often cover the large catastrophe risks of these very projects. Holding equity provides them with a “skin in the game,” aligning their financial interest with the project’s long-term safety and operational success.

8.2 Specific Conditions for Investment

The Investment Directive 2082 sets strict governance standards to protect policyholders’ money, with several key conditions:

- Public Limited Requirement: Insurers are generally directed to invest only in companies that are structured as Public Limited entities. This ensures the hydropower project adheres to higher standards of transparency, regulatory oversight, and publishes regular financial reports.

- Promoter Share Lock-in: If an insurer invests as a Promoter (a Founding Shareholder) in a new hydropower company (creating a subsidiary or associate company), they must obtain “Theoretical Approval” (Saiddhantik Swikriti) from the Insurance Authority. This process requires the submission of a detailed feasibility study and business plan for regulatory scrutiny.

- Board Accountability: The insurer’s Board of Directors bears direct responsibility for analyzing the inherent risks of the project before investing. They cannot rely solely on the project’s prospectus but must conduct independent due diligence, particularly regarding the project’s liquidity profile and asset-liability match.

8.3 Strategic Implication: The Circular Economy

This regulatory framework creates a Circular Financial Ecosystem within Nepal’s infrastructure sector, which operates in several steps:

- Step 1 (Capital Formation): Insurance companies collect premiums from the public.

- Step 2 (Financing): Using the 10% Investment Mandate, insurers inject this capital into Hydropower Projects as equity or debt.

- Step 3 (Risk Transfer): The Hydropower Project, once constructed (or during construction), purchases Engineering and Property Insurance to protect its assets.

- Step 4 (Revenue Recirculation): The insurance premiums for these large policies are paid back to the insurance companies (primarily Non-Life) and Reinsurers.

A prime example of this is the Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Project, where government-owned insurance entities like Rastriya Beema Sansthan (Company) were mobilized to invest equity, effectively keeping the project’s funding and its subsequent risk transfer within the national financial sphere.

8.4 Summary of Investment Limits

The following table summarizes the key mandates for different types of insurers:

Insurer Type | Sector Category | Max Allocation (% of Portfolio) | Key Condition | Source |

Life | Hydro, Tourism, Agri | 10% | Public Ltd Co. | Insurer Investment Directive, 2082 |

Non-Life | Hydro, Tourism, Agri | 10% | Max 5% in one project | Insurer Investment Directive, 2082 |

Reinsurer | Hydro, Tourism, Agri | 10% | Public Ltd Co. | Insurer Investment Directive, 2082 |

9. Critical "Fine Print"s from Dispute Cases

The practical application of insurance policies is often defined not just by their wording, but by the disputes that arise from them. An analysis of decisions from the Nepal Insurance Authority’s Nirnaya Sangraha (Compilation of Decisions) reveals recurring patterns and critical clarifications in hydropower project insurance. These cases highlight specific policy clauses and interpretative stances that every developer, insurer, and regulator must understand. The disputes can be broadly categorized into those involving private Independent Power Producers (IPPs) and those related to the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA).

9.1 Disputes Involving Independent Power Producers (IPPs)

The following table details key arbitration cases, the nature of each dispute, and the regulatory reasoning that provides a precedent for future claims.

Incident | Insured and Insurer | Dispute | Result | Reasoning |

Landslide & Canal Damage A sudden landslide blocked the canal, causing water to overflow and damage the powerhouse and penstock pipe. | Insured:Thoppal Khola Hydropower Co. Pvt. Ltd. Insurer:Prudential Insurance Co. Ltd. | The insurer rejected the claim, arguing the damage was caused by “Rain and Flood” (overflow due to blockage) which they claimed was a maintenance issue, rather than the Landslide itself. They also disputed the premium payment timing for the policy extension. | Insurer ordered to pay (NPR 3,78,000) | The Regulator ruled that the proximate cause was the Landslide (a covered peril). The landslide blocked the canal, leading to the overflow. Since the landslide is insured, the resulting damage is covered. The insurer’s attempt to classify it as a non-covered “water overflow” was rejected. |

Transformer Transit Damage A 132/33 KV Power Transformer fell off a truck during transit from Butwal to Dhalkebar substation. | Insured:Mudbhari and Joshi Construction (Contractor for NEA) Insurer:Everest Insurance Co. Ltd. | The insurer argued the damage (oil leakage and internal core shift) was pre-existing or not consistent with the accident description. They also claimed the “Marine-Cum-Erection” policy did not cover certain consequential damages. | Insurer ordered to pay partial claim (NPR ~2.7 Lakhs) | The Regulator cited the police report confirming the accident. While the full replacement of the transformer was not granted, the insurer was liable for repair costs and oil replacement under the transit (Marine) clause. The policy covers “All Risks” during transit unless specifically excluded. |

Flood Damage to Construction Site Flash floods washed away construction materials, housing, and machinery at the Siprin Khola project site. | Insured:High Himalayan Hydro Construction Pvt. Ltd. Insurer:Himalayan General Insurance (Lead) & National Insurance (Co-Insurer) | The Co-Insurer (National Insurance) refused to pay its 41% share of the claim, alleging the invoices were fake/fraudulent, even though the Lead Insurer (Himalayan) had admitted liability and settled its 59% share. | Co-Insurer ordered to pay (NPR ~35.8 Lakhs) | The Regulator ruled that a Co-Insurer generally follows the settlement decision of the Lead Insurer unless fraud is conclusively proven. National Insurance failed to provide sufficient evidence of fraud to override the Lead Insurer’s assessment and the surveyor’s report. |

Debris Removal after Flood Flood buried the construction site (Headworks/Powerhouse) of Upper Dordi A Hydro. | Insured:Bajra Guru Construction Pvt. Ltd. Insurer:Prabhu Insurance Ltd. | The insurer rejected the cost for “Clearance of Debris”, arguing that the debris came from upstream (foreign material) and was not part of the insured contract works, or that the claim exceeded the specific sub-limit for debris removal. | Insurer ordered to pay (NPR ~40 Lakhs) | The Regulator ruled that under a Contractors’ All Risk (CAR) policy, “Debris Removal” covers the cost necessary to clear the site to resume work, regardless of whether the debris originated from the project or upstream. The insurer cannot arbitrarily deny the removal costs if the site is insured. |

Flood Damage to Track Line/Pipes Flood damaged the track line and headers at the Puwa Khola Hydropower project. | Insured:Peoples Power Ltd. Insurer:Sagarmatha Insurance Co. Ltd. | The insurer rejected the claim stating the damage occurred either before the policy inception or during a gap in coverage. They argued the site logs did not match the meteorological data for the claimed date of loss. | Claim Rejected (Insurer Won) | The Regulator found that the insured failed to provide credible evidence (Site Logs/Meteorological Data) proving the damage happened exactly within the valid policy period. The surveyor’s finding that the damage likely occurred during a non-insured period was upheld. |

Construction Material Damage (Flood) Flood damaged construction materials (cement, rods) stored at the project site. | Insured:Various Hydro Contractors (General Precedent) Insurer:Neco Insurance / Others | Disputes often arise regarding whether materials were “stored properly” or if they were actually at the site designated in the policy schedule. | Variable (Often Rejected if off-site) | The Regulator consistently rules that Contractors’ All Risk (CAR) policies only cover items physically present at the designated “Project Site.” Materials damaged while in transit to the site or stored at a different location (not mentioned in the schedule) are not covered. |

The “Maintenance Period” Trap A bridge (infrastructure similar to hydro) was washed away by the massive Melamchi flood. The policy was in the “Maintenance Period” (after construction finished). | Insured:Chokpu Khola Bridge (Melamchi Area) Insurer:Prabhu Insurance | The insurer denied the claim, arguing the standard Maintenance Period coverage excludes “Acts of God.” | Claim Rejected | The Regulator ruled that standard Maintenance Period coverage protects against defects arising from workmanship, but NOT against “Acts of God” (like the Melamchi flood) unless “Extended Maintenance” covering such perils was specifically purchased. Since the flood was an external force, the claim was Rejected. |

“Foreign Debris” & Clearance Costs A flood buried the headworks. The insurer refused to pay for removing debris that came from upstream (foreign debris), arguing it wasn’t part of the insured property. | Insured:Bajra Guru Construction (Upper Dordi A) Insurer:Prabhu Insurance. | Dispute over whether debris removal costs are covered when the debris originates from outside the project site. | Ordered to Pay | The Regulator ordered the insurer to pay. Under Contractors’ All Risk (CAR), “Debris Removal” is a necessary cost to restore the site. The origin of the debris (upstream vs. site) does not matter if it blocks the insured works. |

9.2 NEA-Related Claims and Sector-Wide Challenges

The NEA and its subsidiaries face large-scale losses, and the sector as a whole grapples with systemic insurance challenges.

Incident | Insured and Insurer | Dispute / Nature of Claim | Result | Reasoning |

Upper Tamakoshi (UTKHPP) Flood and Landslide (Sept 27, 2024) | Insured:Upper Tamakoshi Hydropower Limited (UTKHPL). Insurer: Not explicitly named. | Submission of an insurance claim totaling approximately NPR 2 billion to cover damages to civil structures, electromechanical equipment, and loss of profit. | In Progress.Restoration initiated; partial generation resumed Dec 2024. | The disaster caused an 88-day complete shutdown, damaging desander basins, box culverts, surface control rooms, and a 220 kV transmission tower. |

Bhotekoshi River Flash Flood(affecting Trishuli 3A, Rasuwagadhi, and Trishuli 3B Hub) | Insured:NEA and respective subsidiaries. Insurer: Not specified. | Claims arising from severe damage to headworks and substation equipment due to sudden debris flow. | Restoration Ongoing.Rasuwagadhi experienced inundation of the turbine floor. | Flood detached radial gate lower skin plates and submerged control panels, sensors, and motors, rendering them non-functional. |

Panauti Hydropower Station Flood (Ashoj 2081) | Insured:NEA. Insurer: Not specified. | Damage to powerhouse and headworks; submergence of key equipment. | Non-operational.Plant remains inactive following the flood. | Control panels were destroyed and the forebay pond was filled with debris, requiring a comprehensive restoration plan. |

General Sector-Wide Insurance Context | Insured:Hydropower Developers (NEA & IPPs). Insurer:Domestic and International Reinsurers. | General challenges involving restrictive policy terms and weaknesses in the claims process. | Regulatory Gap.Study initiated to strengthen insurance mechanisms. | High exposure to natural disasters and limited domestic reinsurance capacity lead to elevated premiums and restrictive terms. |

In conclusion, these dispute cases reveal critical lessons for the industry: the importance of establishing the “proximate cause” of a loss, the binding nature of the lead insurer’s decision on co-insurers, the broad interpretation of “debris removal” costs, and the severe limitations of standard maintenance period coverage. For NEA, the scale of recent disasters highlights both the critical importance of insurance and the existing gaps in coverage and the claims settlement process for major public infrastructure.

10. How Insurance Practices Impede Financial Closure

A critical, often underestimated obstacle to achieving financial closure for hydropower projects in Nepal stems from the structural weaknesses of the domestic insurance market and the stringent conditions imposed by international reinsurers. This creates a dependency that can stall project financing, particularly for developments in geographically high-risk areas.

10.1 "Fronting" for Global Reinsurers

The core of the issue lies in the significant disparity between the value of major hydropower projects and the financial capacity of Nepal’s insurance companies. While Nepal has 14 non-life insurers, their individual capacity to retain risk is minuscule. Regulatory frameworks, designed to ensure solvency, restrict an insurer’s retention per risk to a small percentage of their net worth—for instance, no more than 5%. In practical terms, for a 50 MW project costing NPR 10 billion, a local insurer with a net worth of NPR 2-3 billion can only retain a fraction of the risk (e.g., NPR 10-15 crores). The remaining 95-99% of the risk must be transferred to international reinsurers like GIC Re of India, Munich Re, or Hannover Re through “Facultative Reinsurance,” which is a case-by-case transfer for specific, high-value risks. This effectively reduces the role of the Nepali insurer to that of a “front,” while the actual risk—and the crucial decision to insure it—is determined in financial hubs like Mumbai, London, or Germany.

10.2 The "High Hazard" Trap

This dependency becomes a critical liability when a project is located in a zone perceived as high-hazard, such as basins prone to Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) or landslides, a concern magnified by events like the 2021 Melamchi disaster. In such cases, international reinsurers, who bear the bulk of the potential loss, dictate the terms of coverage in ways that can render a project unbankable. Their reactions typically manifest in three ways:

- Refusal of Cover (Capacity Withdrawal): Reinsurers may simply decline to provide facultative reinsurance for projects in specific geographic coordinates they deem too risky. Without this essential backing, the local insurer is legally barred from issuing the policy, completely halting the project’s insurance procurement.

- Imposition of “Unbankable” Deductibles: A more common, yet equally debilitating, reaction is the imposition of excessively high deductibles. In one documented dispute involving Neco Insurance, the reinsurer set a condition: “Subject to an excess of 50% of Sum Insured on each and every occurrence of loss”. This means for a project valued at NPR 1 billion, the developer would have to cover the first NPR 500 million of any loss. Banks will not accept such a policy, as their primary collateral—the project itself—would be effectively uninsured for half of its value.

- Exclusion of Key Perils: Reinsurers may agree to cover the project but exclude fundamental risks like “Flood” or “Landslide.” Since lenders universally require “All Risk” insurance for financial closure, a policy that excludes the primary natural perils of the Himalayan region is worthless for securing financing.

Furthermore, reinsurers employ risk-based pricing using global catastrophe models. For Nepal, already categorized as high-risk, premiums are steep. In particularly hazardous basins, reinsurers apply massive loadings, demanding rates far above the Nepal Insurance Authority’s minimum tariff. This surge in cost can severely impact the project’s financial model, potentially wrecking its Internal Rate of Return (IRR) and rendering it unviable.

10.3 How This Impedes Financial Closure

Financial closure is the point at which lending institutions release funds, contingent upon the project securing a “bankable” insurance policy that guarantees the bank will be repaid even if the project is destroyed. The reliance on international reinsurers creates a vicious cycle, especially in high-hazard basins:

- Bank Mandate: The bank mandates a “Contractors’ All Risk” (CAR) policy covering Flood, Landslide, and GLOF with a standard, manageable deductible (e.g., NPR 5-10 lakhs).

- Insurer’s Limitation: The Nepali insurer, lacking sufficient retention capacity, must seek coverage from international reinsurers.

- Reinsurer’s Stringent Terms: The reinsurer, after analyzing the project’s specific location, responds with an ultimatum, such as agreeing to cover the project only if the deductible for flood claims is set at NPR 10 crores.

- Stalemate:

- The Nepali insurer cannot issue a policy with a lower deductible because it would be legally and financially liable for the difference in the event of a claim.

- The bank immediately rejects the policy because a NPR 10 crore deductible represents an unacceptably high risk for the developer to carry, leaving the bank’s collateral exposed.

- Result: The insurance policy cannot be issued on terms acceptable to the bank. Loan disbursement is halted, and financial closure is stalled, jeopardizing the entire project. This dynamic illustrates how a risk perception shaped in global boardrooms can directly determine the fate of critical national infrastructure.

11. Premium Rate and Average Loss Rate in Hydropower Property Insurance

The pricing of property insurance for hydropower projects in Nepal is a critical factor influencing both the viability of the projects and the stability of the insurance sector. Governed by the Property Insurance Directive 2080 and informed by historical data from sources like the Reinsurance Study 2019 and recent Beema Pratibimba bulletins, the current framework employs a tariff system that sets fixed premium rates. However, an analysis of premium rates against actual loss experiences reveals significant disparities, particularly in the face of Nepal’s high exposure to natural catastrophes. This section examines the current statistics, assesses the adequacy of the existing tariff, and proposes revisions based on risk-adjusted principles, including a hypothetical scenario where the loss rate escalates to 250%.

11.1 Current Premium and Loss Statistics

For operational hydropower projects, the Nepal Insurance Authority (NIA) mandates a tariff-based pricing structure. The base premium rate is fixed at 0.20% (Rs 2.00 per thousand) of the sum insured. However, most projects are required by lenders to purchase Business Interruption (Loss of Profit) coverage, which is priced at 300% of the base rate for a 12-month indemnity period, adding 0.60% to the cost. Consequently, the total effective rate paid by hydropower developers typically ranges from 0.80% to 0.85% of the asset value annually, excluding optional add-ons like terrorism coverage.

In contrast, the loss rates—representing the actual risk—demonstrate volatility driven by catastrophic events. Historical data from the Reinsurance Study 2019 provides insight into two key portfolios:

- Fire/Property Portfolio (Proxy for Operational Hydropower): Between fiscal years 2070 and 2075, this portfolio saw gross premiums ceded to reinsurers amounting to Rs 6.57 billion, while claim recoveries totaled Rs 8.10 billion. This results in an implied loss ratio of approximately 123%, indicating that claims exceeded premiums by 23%, largely due to catastrophic events like the 2015 earthquake.

- Engineering Portfolio (Proxy for Construction Phase): During the same period, gross premiums ceded were Rs 4.49 billion, with claim recoveries of Rs 2.80 billion, yielding a loss ratio of about 62%. While this appears profitable, the sector is prone to frequent total losses, such as floods washing away headworks, as evidenced in disputes like Bajra Guru Construction vs. Prabhu Insurance.

11.2 Analysis: Inadequacy of the Current Flat Tariff

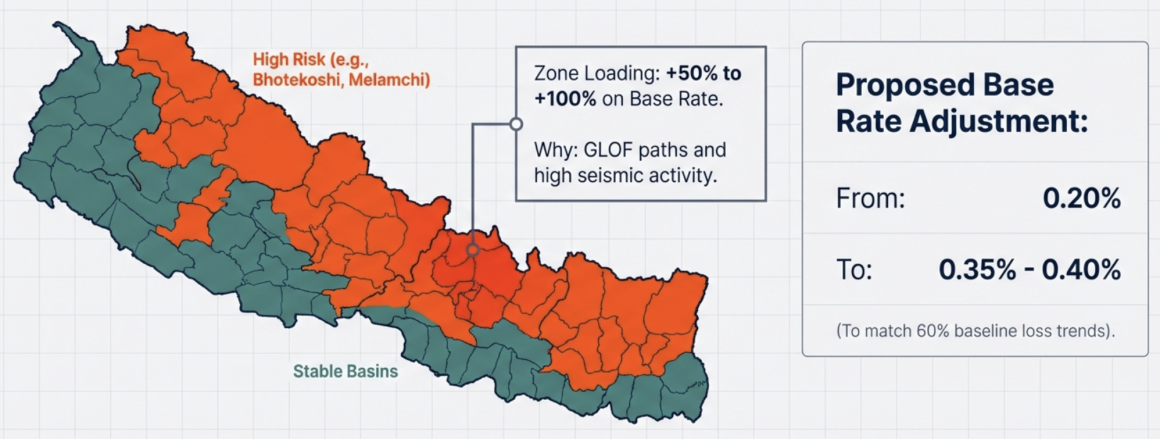

The current flat tariff of 0.20% is inadequately priced for the long-term catastrophe risk profile of Nepal’s hydropower sector. Three key issues underscore this inadequacy:

- Historical Deficit: The loss ratio of 123% in the fire portfolio during catastrophe-prone periods confirms that premiums were insufficient to cover claims, leading to a net outflow of currency and failing to build adequate reserves.

- Reinsurance Market Dynamics: According to Risk Management Guidelines, domestic insurers rely heavily on international reinsurers for capacity. When loss ratios sustain above 60% (as seen in Poush 2081) or spike to 120%, reinsurers often harden terms, demanding rates higher than the NIA’s minimum tariff. This forces local insurers to either absorb losses or reject risks, stifling project insurance availability.

- Lack of Risk Differentiation: The one-size-fits-all rate of Rs 2.00 per thousand applies equally to projects in low-risk zones and those in high-risk areas prone to Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) or landslides, such as the Melamchi or Bhotekoshi basins. This underprices high-risk projects and overcharges low-risk ones, distorting risk-based pricing principles.

11.3 Proposed Revisions to the Minimum Tariff

To align with the Risk-Based Capital (RBC) framework and ensure sector solvency, the tariff structure requires revision from a flat rate to a risk-adjusted model. The following changes could be adequate considering the going loss rates:

- Base Rate Adjustment:

- Current Rate: 0.20% (Rs 2.00 per thousand).

- Suggested Rate: 0.35% to 0.40% (Rs 3.50 to 4.00 per thousand).

- Reasoning: A loss ratio of 60% (current trend) combined with a typical expense ratio of 35% results in a combined ratio of 95%, leaving a slim 5% profit margin with no buffer for catastrophes. Increasing the base rate by 75-100% would build a sustainable catastrophe reserve, ensuring insurers can cover claims without relying excessively on reinsurers.

- Introduction of Geographic Zone Loadings:

- Instead of a uniform national tariff, the directive should incorporate zone-based factors similar to motor insurance. Projects in “red zones” (e.g., high seismic areas or known GLOF paths) should incur a loading of +50% to +100% on the base rate. This would accurately reflect the higher risk and encourage risk mitigation measures.

11.4 Hypothetical Analysis: Assuming a 250% Loss Rate

If the loss rate for the hydropower portfolio were to reach 250%—a scenario possible during a severe catastrophe cycle—the current tariff would be critically insufficient. Assuming an expense ratio of 35%, the combined ratio would be 285%, necessitating a premium increase to break even. The required base rate can be calculated as follows:

- Target Premium Needed: To achieve a combined ratio of 100%, the premium must cover the loss ratio and expenses. Thus, the base rate should be adjusted upward by a factor equivalent to the loss ratio plus expenses. For a 250% loss rate and 35% expenses, the premium needs to be 2.85 times the current rate to break even (since 250% + 35% = 285%, and 100%/285% ≈ 0.35, but more accurately, the rate must increase proportionally).

- Adjusted Base Rate: Applying this factor to the current 0.20% base rate gives 0.20% × 2.85 = 0.57%. However, this simplistic calculation ignores profit margins and reserve building. A more practical rate would need to be higher, perhaps 0.60% to 0.70%, to ensure sustainability. Combined with the mandatory Loss of Profit coverage (0.60% for 12 months), the total effective rate would rise to 1.20% to 1.30%, highlighting the profound impact of extreme loss scenarios on insurance costs.

This hypothetical underscores the urgency of adopting a dynamic, risk-based tariff system that can adapt to evolving risk profiles, ensuring that premiums accurately reflect the true cost of risk and maintain the stability of both the insurance and hydropower sectors.

12. Government Policies and the Shift to Risk-Based Insurance for Hydropower in Nepal

The Nepalese government has enacted several key policies to integrate the insurance sector with hydropower development, positioning insurance as both a risk transfer mechanism and a source of capital. These policies are driving a significant transition from a traditional tariff-based system to a modern risk-based framework, which has profound implications for insurers, developers, and the stability of the energy sector.

The National Insurance Policy, 2080 serves as the overarching framework, explicitly prioritizing “Risk-Based Pricing” and aiming to link insurance with infrastructure development. It mandates coverage for strategic national projects, including large hydropower plants, and encourages the mobilization of insurance funds into productive sectors like energy. Complementing this, the Insurer Investment Directive, 2082 allows life and non-life insurers to invest up to 10% of their total portfolios in hydropower, solar, and renewable energy projects. This policy effectively transforms insurers from mere service providers into equity partners or financiers for Independent Power Producers (IPPs). Operationally, the Property Insurance Directive, 2080 currently governs hydropower insurance under a “Tariff Regime,” fixing premium rates at Rs 2.00 per thousand (0.20%) for material damage, ensuring standard coverage terms across all projects.

The most impactful change underway is the move from a government-fixed tariff system to one where premiums are determined by the specific risk profile of each project. The Property Insurance Directive, 2080 currently sets a uniform rate of 0.20% for operational hydropower projects, regardless of whether they are in a safe zone or a high-risk area prone to landslides or floods. However, Clause 27 of the same directive explicitly states that “Risk Based Pricing” will be implemented for natural disaster risks (e.g., flood, landslide, earthquake), with premiums determined by factors such as geographical location, construction type, and usage. This shift is reinforced by the Risk-Based Capital (RBC) Directive, which requires insurers to hold capital proportional to the risks they underwrite. If an insurer covers a high-risk hydropower project, it must maintain more capital, indirectly necessitating higher premiums to service that capital.

The transition is phased, with a deadline set for Shrawan 2081 (July 2024) for the implementation of risk-based pricing for natural risks. Currently, the RBC directive is active, and insurers are submitting RBC reports, but full deregulation of premiums is gradual, involving pilot projects and data analysis.

12.1 Concerns from Independent Power Producers (IPPs)

Within the regulatory context IPPs highlights several concerns:

- Cost Escalation: Risk-based pricing is likely to increase premiums, especially for projects in high-risk zones. Given that the current tariff of 0.20% is artificially low compared to historical loss ratios (e.g., 123% in the fire portfolio during catastrophes), premiums could rise by two to three times for vulnerable projects.

- Financial Closure Risks: Strict risk-based underwriting may lead to unaffordable deductibles or outright coverage refusal for projects in high-risk areas like the Melamchi basin, making it difficult to meet bank requirements for loans.

- Uncertainty: IPPs prefer fixed costs for predictability. The non-tariff nature of construction insurance has already led to disputes where premiums fluctuate based on reinsurer demands, undermining stability.

12.2 Nepal Insurance Authority's (NIA) Perspective

The NIA views this transition as essential for the sector’s financial health:

- Solvency Protection: The current flat tariff encourages underpricing and unhealthy competition. Without risk-based pricing, a major disaster could bankrupt insurers, leaving IPPs with unpaid claims.

- International Compliance: Moving to RBC and Risk-Based Supervision (RBS) aligns Nepal with International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) standards, enhancing credibility to attract international reinsurers, who are currently hesitant to cover Nepali risks.

- Sustainability: The shift ensures insurers hold sufficient capital to pay claims during catastrophes, moving from a compliance-based to a risk-based approach for long-term stability.

The following table encapsulates the key differences between the current and future systems:

Feature | Current Tariff System | Future Risk-Based System |

Premium Rate | Fixed 0.20% (Rs 2/1000) for all projects. | Variable based on location, construction type, and risk profile. |

Basis | Regulatory Mandate (Directive). | Actuarial & Scientific Analysis. |

Impact on IPPs | Cheaper, predictable costs. | Potentially higher costs for high-risk projects. |

Regulatory Goal | Market discipline (prevent undercutting). | Solvency & Financial Stability. |

2.5 Policy Gaps and Sovereign Risk

It is important to note that the Hydropower Development Policy 2001 and the Electricity Act 1992 contain no specific mandates for insurance, leaving the Insurance Act as the primary regulator. A significant market issue is that developers often purchase the “minimum viable product” to satisfy loan covenants, resulting in policies with low sub-limits and high deductibles that are inadequate during a total loss scenario. Furthermore, as the sole off-taker and a major generator, the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) has historically practiced “self-insurance” due to financial constraints. This creates a massive contingent liability for the sovereign balance sheet, where the cost of reconstructing a failed mega-project competes directly with other national budget priorities.

13. The Interplay Between Risk-Based Capital and Risk-Based Premiums

The transition to a Risk-Based Capital (RBC) framework in Nepal introduces a critical, albeit indirect, mechanism to address the mispricing of risk in the hydropower insurance sector. While the Property Insurance Directive, 2080, currently mandates a fixed tariff (e.g., 0.20% for operational hydro), the RBC directives create a structural conflict by making it financially untenable for insurers to underwrite high-risk projects at artificially low rates. The connection does not lie in the RBC system directly setting prices, but in its ability to penalize an insurer’s balance sheet for writing high-risk business at low rates, thereby forcing a change in underwriting behavior and risk selection.

13.1 The "Capital Charge" Penalty Mechanism

At the heart of the RBC framework is the concept that capital is not a static requirement but a variable cost. The directive calculates a specific Catastrophe Risk Charge for non-life insurers based on their exposure. The formula incorporates factors like Earthquake Risk Exposure (ERE) and the Probable Maximum Loss (PML) of the insurer’s portfolio.

This creates a direct financial squeeze. If an insurer covers a high-risk hydropower project with a significant PML but only collects the low, fixed tariff premium of 0.20%, the RBC formula will require the insurer to hold a substantial amount of capital (e.g., NPR 50 Crores) to back that specific risk. The result is a poor Return on Equity (ROE) for that policy. The premium income is fixed and low, while the capital cost is high, making “underpriced” hydropower risks financially toxic for the insurer’s shareholders. The RBC framework effectively discourages insurers from accumulating such risks merely to show premium growth, as it directly impacts profitability.

13.2 Forcing Risk Transfer: The Reinsurance Valve

The RBC charge is primarily applied to the Net Retained Risk—the portion of risk the insurer keeps on its own books. This creates a powerful incentive for insurers to cede the bulk of high-risk hydropower exposure to international reinsurers to reduce their capital burden.

However, this leads to a strategic checkmate. International reinsurers, unlike local insurers, are not bound by Nepal’s tariff and use global risk models to price risk. For a project in a high-hazard zone like the Melamchi basin, the reinsurer will demand a premium that reflects the true risk, which is often significantly higher than the local 0.20% tariff. The local insurer is therefore trapped: it cannot retain the risk without incurring a punitive capital charge, and it cannot reinsure the risk profitably because the reinsurance cost exceeds the premium it is permitted to charge. This dilemma forces the insurer to either reject the client altogether or lobby the regulator for a special “Non-Tariff” rate for that specific project, effectively creating pressure to break the tariff ceiling out of operational necessity.

13.3 Solvency Intervention Triggers

The RBC framework introduces a “Ladder of Intervention” based on the insurer’s Solvency Ratio (Total Capital / Risk-Based Capital). This acts as a crucial brake on risky underwriting. If an insurer aggressively writes hydropower policies at the low tariff without holding commensurate capital, its RBC requirement will spike, causing the Solvency Ratio to fall below 100%.

At this point, the regulator is legally empowered to intervene by preventing the insurer from declaring dividends, forcing it to raise new capital, or even suspending its license to issue new policies. This mechanism ensures that even if the tariff allows for cheap premiums, an insurer’s ability to sell them is constrained by its capital strength, preventing the systemic risk of an insurer becoming insolvent from underpriced catastrophe exposure.

13.4 Preparation for Full Deregulation

The implementation of RBC is widely seen as a prerequisite for the eventual dismantling of the tariff system. The Property Insurance Directive, 2080, explicitly states the industry’s intended move toward “Risk Based Pricing” for natural disaster risks. The logical link is that the regulator cannot allow insurers to set their own prices until they demonstrate the ability to measure risk accurately. By forcing insurers to build the actuarial models and capital management practices necessary for RBC compliance, the system is preparing the industry for full deregulation. Once RBC is fully stabilized—a process projected for 2027 according to strategic plans—the regulator can confidently remove the tariff, allowing premiums to rise to levels that truly reflect the capital costs dictated by the RBC framework.

In essence, the RBC framework addresses hydropower risk not by directly changing the premium price, but by dramatically increasing the cost of capital for insurers who underwrite high-risk projects at low rates. This fundamentally alters the insurer’s incentives and strategic options, as summarized in the table below.

Action | Tariff System Effect | RBC System Effect | The Combined Result |

Insuring High-Risk Hydro | Premium is capped at a low rate (e.g., 0.20%). | Capital Charge spikes (e.g., requires $5M capital). | The policy becomes unprofitable (Low Premium / High Capital Cost). |

Insurer’s Reaction | Incentive to sell more policies for cash flow. | Cannot sell more without raising capital (solvency ratio drops). | Risk Selection: Insurer stops writing bad hydro risks or demands higher deductibles to lower capital usage. |

This dynamic ensures that even within a fixed tariff system, the principles of risk-based pricing are enforced through the back door of capital adequacy, steering the market toward greater financial stability.

14. Suitable Insurance Products for Hydropower in Nepal: A Forward-Looking Analysis

The current insurance framework for hydropower in Nepal, characterized by a rigid tariff system, Bill of Quantities (BOQ)-based disputes, and reinsurance bottlenecks, is undergoing a strategic transformation. Guided by the National Insurance Policy, 2080, and the NIA’s Strategic Plans, the sector is actively exploring innovative products that better align with the catastrophic risks inherent in Himalayan hydropower development. These alternatives aim to enhance efficiency, fairness, and resilience. The most promising solutions include Parametric Insurance, Catastrophe Bonds, Risk-Based Pricing, and Alternative Risk Transfer Pools.

14.1 Parametric (Index-Based) Insurance

The Concept: This product replaces traditional loss assessment with a pre-defined, objective trigger. A payout is made automatically when a specific physical parameter—such as rainfall exceeding a certain millimeter threshold, river flow levels, or earthquake magnitude—is met, regardless of the actual physical damage assessed on the ground.

Why it Suits Nepal Hydro: This model directly addresses critical flaws in the current system. It eliminates protracted disputes over the “cause of loss,” which are common in events like the Melamchi floods, where arguments rage over whether damage was due to a covered “Flood” or an excluded “Design Defect”. By relying on scientific data, parametric insurance ensures swift claims settlement, providing immediate liquidity for critical recovery efforts like debris removal, a stark contrast to the current system where claims can take years to resolve. The Nepal Insurance Authority (NIA) recognizes this potential and is already in discussions with international bodies like the Asian Development Bank to implement parametric solutions for climate-induced risks.

Practical Example: A 30 MW run-of-river project in the Melamchi basin purchases a parametric flood policy with a trigger of 250 mm of rainfall in 24 hours, as measured by designated satellite and Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) stations. During a monsoon event, recorded rainfall reaches 320 mm. Without any physical surveyor visit, the insurer automatically triggers a pre-agreed payout of NPR 50 million within seven days. The project uses these funds for immediate debris removal and access road restoration.

Premium Pricing: The premium is based on the probability of the trigger event occurring, not the project’s construction cost. For instance, if historical data indicates that rainfall exceeding 250 mm has an annual probability of 2.5% (i.e., a 1-in-40-year event), the insurer might charge a premium of approximately 2.5% of the payout limit. For NPR 50 million of coverage, the annual premium would be around NPR 1.25 million. This represents a straightforward financial bet: the insured pays the premium annually, and the insurer pays out the full sum only if the trigger is hit.

14.2 Catastrophe Bonds (Cat Bonds) & Insurance-Linked Securities (ILS)

The Concept: These are capital market instruments that transfer extreme risk directly to investors, bypassing traditional reinsurance. Investors purchase bonds where they risk losing their principal if a predefined catastrophic event (e.g., an earthquake of a specific magnitude) occurs. In return, they receive high coupon payments.

Why it Suits Nepal Hydro: Cat Bonds are a powerful solution for overcoming the capacity constraints of the international reinsurance market, particularly for high-hazard basins like Melamchi that face rejection or prohibitively expensive terms from reinsurers. By tapping into the deep capital of global financial markets, Cat Bonds provide a much larger pool of risk-bearing capacity. The NIA’s Disaster Risk Management Strategy explicitly endorses “Catastrophe Bonds” and “Insurance-Linked Securities” as essential tools for future disaster risk transfer, acknowledging the insufficiency of traditional insurance alone.

Practical Example: A 100 MW hydropower project issues a Cat Bond with a trigger linked to an earthquake magnitude of 7.2 within a defined geographical radius. Investors buy the bond, providing NPR 3 billion in capital. If the triggering earthquake occurs, the project receives NPR 3 billion from the bond principal to fund reconstruction, and the investors lose their principal. If no disaster occurs during the bond’s term, investors receive their principal back along with high annual interest (e.g., 9-11%).

Premium / Cost Pricing: Instead of a traditional insurance premium, the project pays a high annual coupon (interest rate) to the investors. This cost is determined by financial models that assess the probability and severity of the catastrophic event.

14.3 Risk-Based Pricing (Catastrophe Modeling)

The Concept: This involves moving away from the one-size-fits-all tariff (0.20%) to a premium calculated using catastrophe models that incorporate geological, hydrological, and seismic data to reflect the true risk profile of each project.

Why it Suits Nepal Hydro: The current system is fundamentally unfair and unsustainable, as a project in a safe zone subsidizes one in a high-risk Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) zone by paying the same 0.20% rate. Risk-based pricing introduces fairness by aligning premiums with actual exposure. It also promotes sustainability by ensuring that insurers collect adequate premiums to build reserves for future claims. The NIA, in collaboration with the World Bank, is actively developing a “Nepal Flood Model” and other actuarial tools to facilitate this shift, with policy directives explicitly calling for “Risk Based Pricing” for natural disasters.

Practical Example: Two 40 MW hydropower projects seek property insurance. Project A is in a geologically stable, low-risk basin. Project B is in a GLOF-prone Himalayan valley. Catastrophe models show Project B has a flood probability three times higher than Project A.

- Project A Premium: 0.15% of Sum Insured (below the current tariff due to low risk).

- Project B Premium: 0.45% of Sum Insured (a risk-loaded premium reflecting its higher exposure).

In the event of a flood, the claims process for physical damage remains the same; the key difference is that the premium paid beforehand accurately reflects the risk.

14.4 Alternative Risk Transfer (ART) - "The Pool"